2024 has been dubbed the “year of elections” by many media an academic sources. It is a year in which 40% of the global population is able to vote for their government. This does not include the inevitable countries where a snap election will be held, local elections, referendums, and by-elections. April shows no sign of slowing down.

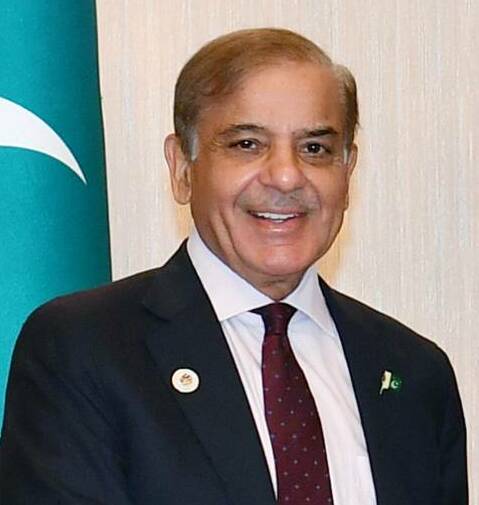

On 2 April, Pakistan held Senate elections. The country has had a bumpy road since independence from the UK in 1947. A number of military coups were held, but the latest saw democracy restored in 2002. A multi-party system has emerged in Pakistan, with three main parties: the centre-right Pakistan Muslim League (N) (PML-N, the N stands for its founder, Nawaz Sharif); the centre-left Pakistan People’s Party (PPP), and the centrist Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI, Pakistan Movement for Justice), which is based on the populist authority of cricketing legend Imran Khan. After the 2018 election to the National Assembly (lower house), no party won a majority but Khan formed a government. In 2022, Khan was removed following a vote of no confidence. In response, Khan produced a diplomatic cable from the US, which criticised Khan for visiting Russia, stated that it would isolate him from the US and Europe, but this was personally linked with Khan rather than Pakistan as a whole, and that “all would be forgiven” should Pakistan change its leader. This riled up his supporters that viewed his removal as a US-backed coup, but also breached state secrets legislation, and started legal proceedings against him. Further charges for corruption were seen as politically motivated by supporters, as was another conviction for an un-Islamic marriage. Since then, the PML-N’s Shehbaz Sharif has served as Prime Minister with support from the PPP. The brother of Nawaz Sharif, who was banned for his own corruption charges and then fled to the UK on supposed medical grounds, Shehbaz’s brother was allowed to return since the Shehbaz premiership began, something in itself viewed as political. In 2024 general elections, the PTI couldn’t run as a party (only as independents) because of a failure to hold intra-party elections, another thing seen as a dirty trick by Khan’s supporters. Even so, the PTI were the largest party in 2024, but many of his supporters say they would have won bigger if not for interference. The Senate is the upper house, with half of the seats chosen every three years. They are elected from the provincial legislatures of Pakistan’s four provinces and the federal capital territory.

On the same day, the American city of Anchorage held its mayoral election. The United States has a two-party system, with the Democratic Party (D) representing the liberal wing of American politics, and the Republican Party (R) more conservative. Though mayoral elections in Anchorage use a non-partisan system, the party affiliation of politicians is known. Incumbent Dave Bronson (R) is running for re-election. Considered a fierce conservative, he won narrowly against Democrat Forrest Dunbar in 2021. Independent Suzanne LaFrance, former chair of the city’s legislature, seemed to be his main opponent in this race. As early results come in, it looks likely Bronson and LaFrance will head to a runoff.

On 4 April, Kuwait held general elections. Kuwait became a sheikhdom in 1752, and in 1899 decided to become a British protectorate to ward off the Ottoman Empire. This lasted until 1961, when the treaties ended, leading to full independence and the sheikh becoming the Emir of Kuwait. Elections for a Constitutional Convention were held that year, with the first regular elections in 1963. However, the parliament only has limited power. The Emir appoints the prime minister, who appoints a cabinet, meaning that power is vested in the royal house. After 1963, elections were held every four years until 1975. In 1976 the Emir Sabah Al-Salim Al-Sabah suspended the constitution and parliament, claiming it “acted against the nation”, and elections did not happen until 1981, by which time he had died. In 1985, elections were held again, but another suspension took place, this time by Emir Jaber Al-Ahmad Al-Sabah. Eventually, elections were held in 1990, but only for half of the body, amidst protests. In 1990, Iraq invaded and annexed Kuwait, and the US stated that help would only come with the restoration of democracy. Thus, after the US liberated Kuwait in 1991, elections were held in 1992, with anti-government candidates performing well. Elections were held again in 1996, 1999, and 2003. In 2006 elections, women could vote for the first time. Though political parties are not legal in Kuwait, some quasi-party “political groups” started to emerge. This included the centre-left Popular Action Bloc. Elections were held again in 2008 and 2009; in the latter case, the parliament was dissolved because the govermnent had resigned to avoid questioning: this was supposedly “abuse of democracy” by the parliament to challenge a royal-backed administration like this. Elections were held in February 2012, but court declared them “invalid” because the old body should not have been dissolved, and held another one in December. These were also annulled, and elections were held again in 2013. Elections were held again in 2016, 2020, and 2022. However, the 2022 election was held again as the dissolution of the 2020 parliament was ruled invalid. This was seen by opposition as an attempt to stifle them, as they had criticised the government and forced some out in no-confidence votes. The opposition still won a majority. 41 of fifty members were not connected to any political group. This time, the body was dissolved because an MP “insulted the Emir”, Mishal Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah, who took the role in December following the death of his half-brother. The results showed nothing that would indicate an end to the dispute between parliament and Emir.

On the same day, Belarus held elections to its upper house, the Council of the Republic. Belarus was part of the Kievan Rus’ state from which both Russia and Belarus derive their name. However, this empire waned and by the thirteenth century, it was part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. In the Union of Krewo, the rulers of Lithuania and Poland were joined in marriage, and in 1569 the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was formally founded, which Belarus was part of. However, in the eighteenth century its power waned and Russia took advantage, taking Belarus near the end of the century. After the communist revolution in Russia (1917), they signed an unequal treaty with Germany to exit World War I, losing Belarus. Both the Poles and Russians attempted to suppress the Belarusian language and assimilate it into their own, but in the nineteenth century Belarusian nationalism was sparked. A German puppet state, the Belarusian People’s Republic, was created, but then went into exile. After further developments, Belarus would be divided between Poland and Soviet Russia. Lithuania and “Belorussia” were part of the same republic, but Lithuania managed to win independence. It became the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic (Byelorussian SSR), which joined the Soviet Union when it was created in 1922. The Soviet Union invaded Poland and took the rest of Belarus in 1939. After Germany’s 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union, Belarus was occupied until 1944. After the end of World War II, Poland took German lands, but the Soviet Union kept most of Byelorussia, giving it its current borders. The Soviet leadership encouraged Russian-speakers to move there, successfully attempting a decline in Belarusian national identity: even today, Russian is the most common language in Belarus, and the current government encourages Russification. Under Mikhail Gorbachev, the Soviet Union began to decline, and different ethnicities began fighting for independence, and an opposition, nationalist Belarusian Popular Front was tolerated. In 1991, strikes related to price increases spiralled, and by the end of the year, the country was independent, with the name Republic of Belarus. A presidential election was held in 1994. It was won easily by independent Alexander Lukashenko. Lukashenko had made a name for himself as an anti-corruption crusader, and as a populist. He promoted the Russian language, close links with Russia, and changed the state symbols back to those resembling Soviet-era ones. Another referendum in 1996 further gave Lukashenko initiative. By the time of the next presidential election in 2001 (which was extended) by the referendum, he had pretty undisputed power. He won over 80% of the vote in every other election: in 2006, 2010, 2015, and 2020. In 2020, he had a challenge to his rule as the popular opposition figure, Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, accused him of cheating her out of a win, leading to mass protests. However, these were suppressed, and Tsikhanouskaya leads a sort of government-in-exile. Though Lukashenko was seen as pro-Russian, he also wanted to play the West off of Russia to an extent. However, after the invasion of Ukraine by Russia in 2022, Belarus has been seen as little more than a client state of Russia by the West. A referendum three days after the invasion allowed Russian nuclear weapons to be placed inside Belarusian territory. Parliamentary elections in 2024 saw all seats won by pro-government candidates, and these indirect elections were the same. Lukashenko will try to tighten the state apparatus to avoid a repeat of the protests when he runs again in 2025.

On 6 April, Slovakia held the second round of its presidential election. When Czechoslovakia’s autocratic communist system was dying, different movements emerged in the Czech and Slovak parts of the federation, which then became political parties. The Slovak leader was Vladímir Mečiar, whose intransigence to the Czechs was key for Slovakia getting independence. He became Slovakia’s first Prime Minister, and was accused of corruption, and even autocracy in his time. He was defeated by a large coalition of opposition parties in 1998, which lasted until 2006, when Robert Fico of the Direction – Social Democracy (or Smer in Slovak) won the election. Though pretty much every country in the EU has a party like this, using a red colour, a rose in its logo, and a name like “Labour”, “Social Democrats”, or “Socialist”; which were all basically the same be they in Norway or Portugal, this party was suspended from the Party of European Socialists (PES) after going into coalition with the hard-right Slovak Nationalist Party (SNS). Fico was removed after a large coalition was needed to do in 2010, but this only lasted until 2012, when Smer won a majority. In 2016, he lost his majority and was forced into coalition with the SNS again. Fico lasted until 2018, when a journalist, Ján Kuciak was murdered whilst looking for Slovak connections with the Italian mafia. This led to huge protests and Fico resigned, with his deputy Peter Pellegrini replacing him. Fico was considered a social conservative and populist despite his party’s red (or at least pink) name. The anti-corruption and broadly conservative Ordinary People and Independent Personalities (OĽaNO) party won in 2020, but they had a bumpy ride as well and new elections were needed in 2023. By then, Pellegrini had split from Smer, forming his own party, known as Voice – Social Democracy (or Hlas). This was meant to be a more pro-European alternative to Smer, although it still was reluctant to adopt social liberalism in Slovakia. This allowed Smer to be taken over by Fico again, and become even more socially conservative, pro-Russian, and taking a similar line to Hungary regarding the European Union: not threatening to leave, but simulataneously critical. He is also populist in style and a large critic of the media. With OĽaNO thumped in the election, Smer became the largest party, and joined coalition with Hlas and the SNS, allowing Fico to become Prime Minister again. Pellegrini became Speaker, and both Smer and Hlas were suspended from PES; the parties began to appear pretty indistinguishable. The main opposition was in the form of Progressive Slovakia (PS), a liberal party in both economic and cultural senses of the word. It was PS politician Zuzana Čaputová who was elected President in 2019, defeating Smer-backed Maroš Šefčovič. Šefčovič basically ran a conservative campaign in that race. Čaputová did not run again, and two candidates reached a runoff. Peter Pellegrini, running with Smer and Hlas’ endorsement, won 37.0%, and came second. The opposition selected Ivan Korčok, an independent diplomat who was Minister of Foreign Affairs, and won 42.5%. Štefan Harabin, a former judge considered to be on the right but without party, won 11.7%. Most of these votes were thought to go to Pellegrini, who is expected to win in the second round. However, polls tightened in the days before the election. This led to a closer race, but Pellegrini still won with 53.1% of the vote, helping the government’s power.

On 7 April, Poland held the first round of local elections. Poland, like Czechoslovakia, was part of the Warsaw Pact of the Soviet Union and the latter’s satellite states. All had a one-party system led by a communist party. Poland’s Solidarity Movement began as an independent trade union, apart from the government. This spearheaded the opposition to communist rule, and partially-fair elections were allowed in 1989, where the union’s political movement, the Solidarity Citizens’ Committee or KO “S”, won nearly every contested seat. The communist system ended when the communist satellite parties broke and backed the KO “S”, allowing a non-communist government to be formed. The communist party had basically disappeared by the time the 1990 presidential election was held, which was won by veteran solidarity leader Lech Wałęsa. Howver, Poland would become a parliamentary country, albeit with a stronger presidency than many similar countries in Europe (including Slovakia): in part because such a popular figure had that office. The first election in 1991 saw a very splintered parliament with 29 parties winning seats. The liberal wing of the KO “S” under Prime Minister Tadeusz Mazowiecki had split into the Democratic Union, which won the most seats. Meanwhile, the Democratic Left Alliance (SLD) emerged as a coalition of the left, and many ex-communists. Ten parties even won double-figure totals including the right-wing Catholic Electoral Action (WAK), and the agrarian centrist Polish People’s Party (PSL): the rump of the KO “S” came ninth. This messy situation led to three Prime Ministers before another election was held in 1993. This time a tough threshold was introduced of 5% for parties and 8% for coalitions, and only seven won seats: the SLD, the PSL, the Democratic Union, the centre-left Labour Union, the right-wing Confederation of Independent Poland, the centre-right Nonpartisan Bloc In Support of Reforms (BBWR), and the German Minority Electoral Committee. An SLD-PSL government was formed in this time, although there were still three PMs because of squabbling between the two. In 1997, a number of parties coalesced around the Solidarity Electoral Action (AWS) coalition, which won the election. The agrarian-socialist coalition was damaged, as even though the SLD held mostly firm, the PSL got battered. The centrist Freedom Union, which succeeded the Democratic Union (UW), the conservative Movement for the Reconstruction of Poland (ROP), and the German Minority also won seats. This led to an unbroken four-year term in office for Jerzy Buzek in an AWS-UW coalition. The next election was in 2001, by which time people had had enough of the AWS following a difficult period. An SLD-Labour Union alliance won the most seats, with the Civic Platform (PO) emerging as the main opposition, being a liberal, centre-right split from existing parties. The more populist left Self-Defence of the Republic of Poland (SRP) party came third ahead of the conservative Law and Justice (PiS), which split from the AWS. It was the brainchild of the Kaczyński brothers, Lech and Jarosław; the former being Justice Minister in the Buzek government. The PSL, the right-wing League of Polish Families (LPR), and the German minority also won seats, but the AWS lost all 201 seats in parliament. The agrarian-left coalition was revived. In 2005, the SLD was smashed and came fourth. PiS were top ahead of the PO and SRP. The LPR, PSL, and German Minority also won seats. Also that year, Lech Kaczyński became President, beating PO leader Donald Tusk in a runoff. Jarosław Kaczyński became Prime Minister in 2006, thus creating a sibling duo of President and PM. However, their coalition with the SRP and LPR was broken in 2007 when the SRP leader was linked with corruption. In the resulting election, the PO beat PiS. The Left and Democrats (LiD) which included the SLD, the PSL, and the German Minority also won seats. Donald Tusk became PM in a PO-PSL coalition, and served a stable term until 2011. In 2010, a plane crash in Russia killed 96 people including Lech Kaczyński. Thus, Jarosław Kaczyński ran for president instead of his brother, but lost to PO candidate Bronisław Komorowski. In 2011, Tusk was re-elected (something that had pretty much never happened since the return of democracy), with the PO ahead of the PiS again. Palikot’s Movement (RP), a more left-liberal party created by a PO splitter, was third, with the PSL, SLD, and German Minority also winning seats. Tusk left to become President of the European Council in 2014. However, in 2015 President Komoroswki lost to PiS’s Andrzej Duda. The general election saw PiS win a majority, ahead of PO. The other parties to win seats were the right-wing Kukiz’15, (named after its leader Paweł Kukiz), the centrist Modern, the PSL, and the German Minority: not a single left-wing party won a seat. After this, Jarosław Kaczyński would not become PM, but prefer to run things as PiS leader. Beata Szydło became PM, but was removed in 2017 simply because she lost Kaczyński’s confidence. This was due to the fact that relations with other EU countries, and the EU itself declined in her tenure. The PiS government was strongly criticised in Brussels because of certain illiberal moves: especially the negating of the independence of the judiciary, and the neutrality of the public television station. Mateusz Morawiecki became PM in 2017. In 2019, PiS’ United Right coalition won another majority: this consisted of PiS, the far-right United Poland, the centre-right Agreement, and some independents and smaller parties. PO led a “Civic Coalition” (KO), with Modern and other small parties, but this flopped and came second. The Left coalition won some representation, with the SLD, centre-left liberal Spring, and others winning seats, while the PSL-led Polish Coalition came fourth. The Confederation Liberty and Independence, which mixed right-wing populism and libertarianism, came fifth, with the last seat going to the German Minority. This did set in stone the main five parties in poland: PiS and the Confederation on the “right”, and the PO, Left, and PSL on the “opposition” (which can hardly be called the “left”, but may be called the liberal or progressive camp). In 2020 Duda was narrowly re-elected against the KO’s Rafał Trzaskowski. As time went on, Poland’s opposition began to view their position as fighting for democracy itself, while PiS and the state media talked about them defending Poland from hostile forces in the EU, media, and global elites (like Fico’s Slovakia and Hungary, PiS did not want Poland to leave the EU but frequently clashed with Brussels). In 2021, the Agreement left the coalition, costing them their majority. The United Right coalition, including PiS, the renamed Sovereign Poland (formerly United Poland), and Kukiz’15 still came first, but were dented in 2023. The KO, mostly of the PO but other smaller parties like Modern, were second. The PSL formed an alliance with the new liberal Poland 2050 party called the Third Way (TD) which came third. The SLD and Spring merged into the New Left, which alongside the Left Together party formed The Left coalition which came fourth. The Confederation and its ally, the right-wing New Hope, were fifth. KO, TD, and The Left formed a coalition, with the returning Donald Tusk as PM, despite Duda trying to delay this. Duda has proved a thorn in the Tusk government’s side, trying to block a number of bills. Notably, Tusk’s government removed most figures associated with the state televsion company, despite an attempt from old figures and PiS politicians to occupy the building, now suddenly concerned with media fairness, which had been the cry of the opposition to them for the last eight years. It is this messy situation in which these elections, last held in 2018, take place. It is the first test for the Tusk administration, with all sub-national bodies and mayoralties being elected. Independents normally hoover up a lot of seats here, and the PSL do better than national elections. In the end, it was a pretty good day for PiS, but the government held on to the main urban centres. In rural areas, PiS did a good job of mobilising voters.

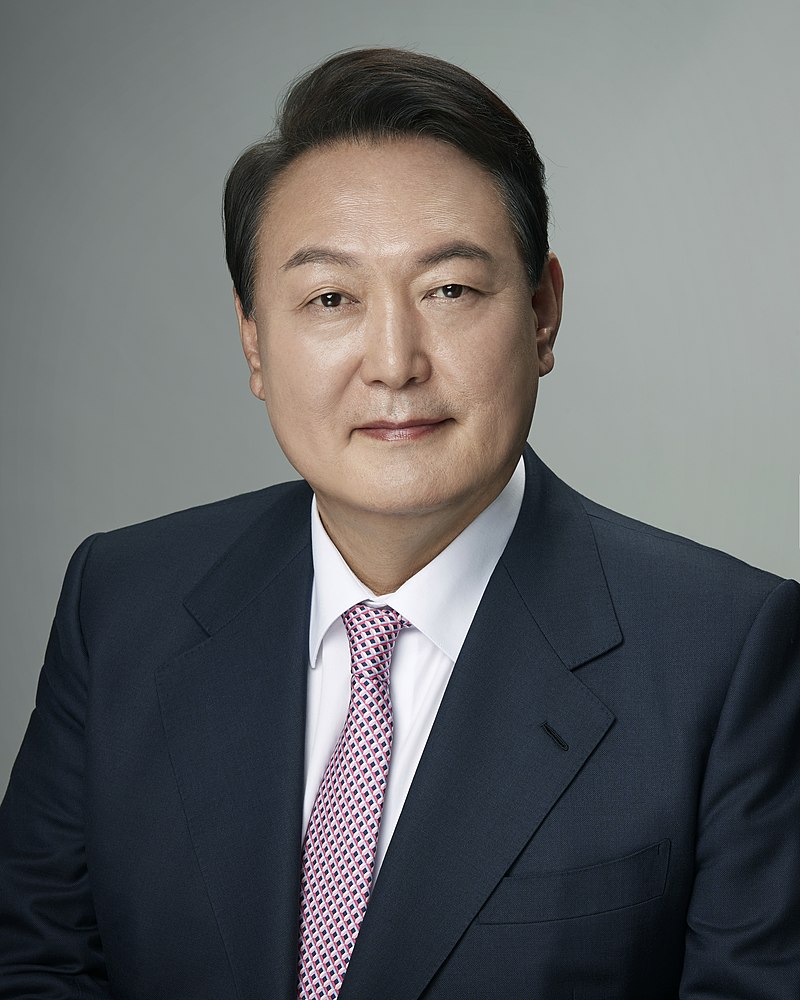

On 10 April, South Korea held parliamentary elections. Korea had traditionally been a kingdom of its own and was known as a “hermit kingdom” thanks to its isolationism, although this waned as influence was fought over by great powers. After the Japanese victory in the Russo-Japanese War, Japan quickly moved to make Korea a protectorate in 1905, and then in 1910 a part of Japan. However, after the defeat of Japan in World War II, Korea was divided into Soviet (northern) and American (southern) areas, before a negotiation for a new government would be created. However, the Soviet Union refused to let the UN team into northern areas to hold elections, and so the new UN-backed government only ruled in the former American area. Instead, in the Soviet area, different elections were held with a communist autocratic government. After a stalemate in the Korean War, both sides continued to consider themselves the sole government of all of Korea (although North Korea dropped their goal of peaceful unification in 2024), but the Republic of Korea in practice only controls South Korea, and always has. The US military elections of 1946 were the first held in what would become South Korea, and then the 1948 Constitutional Assembly elections. That year, nearly half of the seats were taken by independents, but the conservative National Association for the Rapid Realisation of Korean Independence (NARRKI) won the most seats of any party, with the liberal bourgeois (that is to say, of the traditional landed gentry, and in practice right-wing) Korea Democratic Party (KDP) second. NARRKI leader Syngman Rhee was named President by the body, and the Republic of Korea was proclaimed. In 1950, the KDP had merged to form the Democratic Nationalist Party (DNP), and they and the Korea Nationalist Party (KNP), which was inspired by the Chinese nationalist government on Taiwan, won the most seats, followed by NARRKI, who after independence had become simply the National Association. Realising he would lose an indirect election, Rhee passed a constitutional amendment under duress to make the 1952 election direct. He merged NARRKI with some other organisations, including the far-right, to form the Liberal Party (liberal here basically meant anti-communist and little else). However, the far-right influence soon was dropped, and he ruled as a conservative autocrat, winning the election with 74.6% support. In 1954, the Liberal Party won a majority, with most other seats going to independents, but the DNP, National Association (which stayed extant despite the formation of the Liberal Party), and KNP won seats. Rhee defeated Cho Bong-am, a liberal independent, in 1956, but Cho’s 30.0% was a surprise; in 1959 he was executed for espionage. The DNP became the Democratic Party in 1955, a liberal conservative reformist party. The Liberals won a majority in 1958, with the Democrats the main opposition. In March 1960, Rhee had gotten a constitutional amendment passed to exempt himself from term limits, and his Democratic opponent died a month before the election. However, the Democrats had momentum in the vice-presidential election, and when official results showed their candidate Chang Myon on just 17.5%, protests erupted, especially when a young protester’s body was discovered. The police were ordered to shoot, and this only caused further protests. Eventually they lowered their weapons and Rhee had no recourse but to resign. The Democrats won a landslide in the election, and the parliament elected Democratic leader Yun Posun as president. A parliamentary system was established, with Chang Myon as PM. However, instability in this led to a military coup led by General Park Chung Hee, Chairman of the Supreme Council for National Reconstruction. In 1963, the constitutional order was restored, but the only difference was Park ruling as a civilian dictator instead of a military one (under American pressure to cut off aid if he did not). He formed a Democratic Republican Party (DRP), while his opponents formed the Civil Rule Party (CRP). Park narrowly beat Yun (46.7% to 45.1%) in presidential elections in 1963, but easily beat the CRP in legislative elections, both of which had the regime’s finger on the scale. By the next set in 1967, the CRP had merged into the New Democratic Party (NDP). Park beat Yun again, and the DRP won a majority again. In 1971, Park beat NDP candidate Kim Dae-jung, and Kim still managed to get over 45% of the vote. The NDP also made gains in parliamentary elections. Park was threatened, and in 1972 launched a self-coup called the October Restoration. Among changes were an electoral college with no parties, and all of those elected voted for Park. A third of the seats in parliament were also elected by the college after being chosen by the President, though DRP and NDP members were also elected. Park was assassinated in 1979 by a close confidant, and his Prime Minister Choi Kyu-hah was elected to finish his term. However, the military leader Chun Doo-Hwan took control in a coup, and another coup months later by the same led to Chun being elected President unanimously. He allowed political parties for the 1981 election, forming his own Democratic Justice Party (DJP), while liberals formed the Democratic Korea Party (DKP). Chun was re-elected president by a DJP-dominated Electoral College, while the DJP beat the DKP to a majority in parliamentary elections in 1981. In 1985, the DJP won another majority. The New Korean Democratic Party (NKDP), who viewed the DKP as merely a satellite and themselves as the “true opposition”, beat the DKP to second. Mass protests began in 1987 and brought about fair elections later that year. However, the DJP candidate Roh Tae-woo still won, with the opposition split between veteran opposition leader Kim Young-sam from the Reunification Democratic Party (RDP), and Kim Dae-jung, who formed the Peace Democratic Party (PDP). The conservative, pro-Park New Democatic Republican Party came fourth. In 1988, the DJP won general elections ahead of those three, with the PDP the largest opposition. The DJP then merged with the RDP and New Democratic Republican Party to form the Democratic Liberal Party (DLP). The PDP renamed and then merged to form the Democratic Party. The DLP lost the majority it had gained through mergers in 1992, but still beat the Democrats. The DLP candidate in 1992 was Kim Young-sam, once of the opposition, and he beat the Democrat Kim Dae-jung. Businessman Chung Ju-yung also ran a strong third party campaign from the centre-right Unification National Party. In 1996, the DLP (which had renamed itself to the New Korea Party or NKP) came first again. Kim Dae-jung had retired, but then came back and formed his own National Congress for New Politics (NCNP). The right-wing United Liberal Democrats (ULD) beat the official Democrats (who had merged into the United Democratic Party). The NKP then merged with the United Democrats to form the Grand National Party (GNP). However, their candidate Lee Hoi-chang lost to the NCNP’s Kim Dae-jung, who finally won over 25 years since his first crack at the top job. Former judge Lee In-je had a strong third-party bid. In 2000 parliament was split, with the GNP beating the Alliance of DJP: a coalition between the NCNP merger known as the Millenium Democratic Party (MDP) and the United Liberal Democrats (DJP were the leaders’ initials). The GNP was ahead by just one seat. However, in 2002, the MDP’s Roh Moo-hyun still beat the GNP candidate Lee Hoi-chang. Roh left the MDP to form the Uri Party (Our Party), for which the GNP and MDP tried to impeach him. However, this meant in 2004 the MDP lost nearly all support, with the Uri Party winning a majority and the GNP in opposition. In 2007, GNP candidate Lee Myung-bak won the presidency easily, with the Uri Party having become the Grand Unified Democratic New Party (GUDNP) and saw their candidate Chung Dong-young under perform. Lee Hoi-chang ran as an independent this time but still performed well in third. In 2008, the GNP won a majority. The GUDNP had merged into the Democratic Party, which lost seats and became the opposition. In 2012, the GNP renamed to the Saenuri Party (New Frontier Party). The Democratic Party merged with a small party to become the Democratic United Party (DUP). Saenuri won a majority, but the DUP made gains. In the presidential election, Saenuri candidate Park Geun-hye, daughter of Park Chung Hee, narrowly beat DUP candidate Moon Jae-in. The DUP had renamed, merged, and renamed again to form the Democratic Party of Korea (DPK), which won the most seats in 2016 elections, with one more than Saenuri. The centrist People Party also did well in third. In 2016, Park was impeached, and in 2017, removed for abuse of power and corruption. The election saw the DPK’s Moon easily beat Saenuri (which was renamed the Liberty Korea Party or LKP) candidate Hong Joon-pyo and People Party candidate Ahn Cheol-soo. A new system was introduced for the 2020 parliamentary election, which was meant to help smaller parties. However, the big two parties got around this by introducing satellite parties. The DPK and its satellite Platform Party won a majority. The LKP had merged to form the United Future Party (UFP), which was the opposition along with its satellite Future Korea Party. The UFP then renamed itself the People Power Party (PPP). In 2022, PPP candidate Yoon Suk Yeol narrowly beat the DPK’s Lee Jae-myung. At the time, there was some dissatisfaction with the DPK. Notably, the PPP had managed to tap into rising anti-feminist sentiment amongst young men in the country, while the DPK’s own credentials were rocked by accusations that the DPK Mayors of Seoul and Busan had been accused of sexual harrassment, leading to by-elections where the PPP won big. Yoon’s approval ratings took a hit due to inflation but are currently pretty decent, hovering between 35% and 40%. The DPK are still ahead of the PPP in the constituency vote for the election. For the proportional vote, the satellite parties are being used: for the DKP the Democratic Alliance of Korea (DAK), and for the PPP, the People Future Party (PFP). Controversial progressive former Justice Minister Cho Kuk has formed his own party, the Rebuilding Korea Party (RKP). This is only going to contest the proportional seats (of which there are far less than constituencies), where it is expected to be the main opposition to the PFP, with the DAK taking a backseat. This election was a big test for the PPP and Yoon, and a chance for both them and the opposition to get some momentum, but the next presidential election is not until 2027. In the end, the DPK won a big majority, and also came second ahead of the RKP for the PR vote. The PPP was in gloomy moods at the end of the election night, while the DPK and RKP went on the attack.

On 13 April, the Australian constituency of Cook held a by-election. Australia started with three parties, the left-of-centre Labor Party, and the Protectionist and Free Trade Parties. These merged to form the Liberal Party, and then after a series of mergers, splits, and rebranding, finished at the Liberal name again. In rural areas, they are joined in Coalition (and sometimes competition) with the National Party. The Coalition is the main conservative force compared to Labor, a social democratic party. Cook is in the state of New South Wales, having been created as a safe Liberal seat in 1969, the year John Gorton’s Coalition narrowly held on to their majority. Don Dobie was elected as Liberal MP with a big swing to Labor, and in 1972, Gough Whitlam’s victory, Dobie lost narrowly to Labor’s Ray Thorburn. Thorburn just beat Dobie in a 1974 rematch as Whitlam won another majority, but in 1975’s Coalition landslide under Malcolm Fraser, Dobie beat Thoburn easily with an 8.3% swing. Fraser won another landslide in 1977 and Dobie beat Thoburn easily again, and though Fraser’s majority was reduced in 1980, Dobie again beat Thoburn with ease. In 1983, Bob Hawke’s Labor won a landslide, but Dobie survived a 5% swing against him. In 1984, despite an even bigger Labor landslide, Dobie won back most of the ground he lost the year previous. An even bigger landslide in 1987 still saw Dobie win easily. In 1990, Hawke’s Labor won again easily, but Dobie increased his own share. In 1993, Labor under Paul Keating won again but Dobie survived a swing against him comfortably. Dobie retired for the 1996 election, but Liberal Stephen Mutch won easily as the party won a landslide under John Howard. Mutch was defeated in Liberal preselection for the 1998 election by Bruce Baird, who won the seat easily as Howard won a big majority. In 2001, Howard’s Coalition won again and Baird held on easily. Howard increased his majority again in 2004, and Baird won easily again. Even in Labor’s landslide win over Kevin Rudd in 2007, Liberal Scott Morrison easily won re-election (although there was a nearly 7% swing against him). Morrison had worked for the Liberals but left the party temporarily to become managing director of the national tourism agency. However, he returned and won the seat in 2007. Labor lost their majority in 2010, although Julia Gillard managed to win enough support. Morrison won with a 6.3% swing. In 2013, the Coalition under Tony Abbott won a landslide, with Morrison winning over 60% of the primary vote. Morrison was named Minister for Immigration and Border Protection, and then in 2014 reshuffled as Minister of Social Services. Growing in popularity, when Abbott was defeated by Malcolm Turnbull in a leadership spill, the latter appointed Morrison Treasurer. In 2016, Turnbull narrowly won another majority, and Morrison easily held on to Cook. However, Liberal vultures began to surround Turnbull. In 2018, Turnbull pre-empted a challenge by calling a leadership spill on himself, where he beat right-wing hardliner Peter Dutton. However, this gave impetus to some who initially stood by Turnbull. Thus, another leadership spill was called. Turnbull was considered a moderate, and both Dutton and ‘continuity candidate’ Julie Bishop ran. Thus, Morrison could emerge between the two as a compromise candidate, and won. He became Prime Minister. In 2019, despite naysaying polls, he led the Coalition to another majority. However, his second term was tumultuous, with bushfires giving momentum to left-wing critics of climate change. His response to the COVID-19 pandemic was reviewed mostly positively, but he was criticised for mishandling of sexual misconduct allegations towards Coalition politicians. This led to the Liberals losing ground in suburban seats, and the general idea that they had a ‘woman problem’. The ‘teal independents’ (a combination of green and Liberal blue) rose in popularity, being mostly female candidates in suburban Liberal seats, while the National vote held up in rural areas. This led to Labor under Anthony Albanese winning a majority. Morrison held onto Cook easily, but his power was gone: he resigned as Liberal leader, replaced by Dutton, and scandal broke out that he had secretly sworn himself in to several ministerial positions as PM. He is now retiring from politics, but this by-election will change little. The Liberals have won every election here since 1975, and Labor have announced they are not bothering with a candidate. Liberal candidate Simon Kennedy was considered a shoo-in for this seat, and so he was, easily beating the Green Party’s Martin Moore.

On 15 April, the Canadian provincial constituency of Fogo Island-Cape Freels in Newfoundland and Labrador will have a provincial by-election. Canada has a two-party system, with the Liberal Party and Conservative Party, since federation. The Conservatives renamed themselves the Progressive Conservatives, and have been joined by two third parties: the New Democratic Party (NDP), to the left of the liberals, and the Quebec separatist Bloc Québécois (Quebecer Bloc). In the 1993 federal election, the Progressive Conservative lost votes to the Reform Party of Canada, which then became the Canadian Alliance. After a while, it became clear that having two conservative parties would lead to perpetual Liberal victory, so the two merged into the Conservative Party of Canada. However, the Reform Party was a mostly western phenomenon, and in Newfoundland and Labrador the old Progressive Conservative name survives. In the last provinical election, the incumbent Liberals won a majority. The Progressive Conservatives were in power from 2003 to 2015, but lost that year to the Liberals of Dwight Ball in a landslide. In 2019, Ball’s Liberals were reduced to a minority. Ball resigned in 2020 amidst accusations of cronyism. His replacement was Andrew Furey, who won a majority in 2021. The Progressive Conservatives are still the main opposition, with the NDP and a few independents picking up the remaining handful of seats. PC leader Ches Crosbie resigned, and in 2023 Tony Wakeham was elected leader. However, it was a difficult start as interim leader David Brazil resigned, and the Liberals gained the seat in a by-election. This election was caused by the death of Liberal MHA Derrick Bragg, and is a safe Liberal seat, meaning Liberal candidate Dana Blackmore should easily beat rivals Jim McKenna (PC) and Jim Gill (NDP). The seat was created in 2015, and always won by Bragg with relative ease, although it was a bit closer in 2019. In 2021, Bragg got 61.1%, the PC candidate 36.6%, and Gill 2.3%. The federal Liberals are currently unpopular, and so the provinical Liberals have gone with a new branding which has the name FUREY in big letters and the words “Newfoundland & Labrador Liberals” in small font below.

On 17 April, Croatia will hold parliamentary elections. Croatia had been an independent country and part of another country in various points in its history. A Duchy of Croatia emerged in the seventh century, which became a kingdom in the tenth. After a succession crisis, in 1102 there was a union of the crowns with Hungary. The Hungarian crown itself was united with the Austrian one in 1526. In 1868 it merged with Slavonia, but remained part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The Austro-Hungarian Empire fell apart after defeat in World War I and Croatia-Slavonia merged into the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes: Yugoslavia. Elections were held in Yugoslavia, with a multi-party system at this stage which was mostly non-ethnic. A shooting in parliament led to parliament being prorogued by King Alexander I, who formally renamed the country Yugoslavia, hitherto just a nickname. He established a royal one-party dictatorship under the Yugoslav Radical Peasants’ Democracy party. This was known as the 6 January Dictatorship. This was seen not just as an infringement of political rights, but ethnic dominance of a Serb over Croats and Slovenes. Croatian nationalist sentiment began to rise in the form of the Ustaše (uprisers). Alexander was assassinated by Bulgarian revolutionaries with Ustaše support in 1934. As time went on, fascist Germany and Italy were harboring expansionist aims, so Prince Paul (regent for the minor King Peter II) signed the Tripartite pact with Germany, Italy, Japan, Hungary, Romania, puppet Slovakia, and Bulgaria; this made Yugoslavia formally part of the ‘Axis’. By now, Germany was at war with the UK. Mass anti-Axis, pro-British protests ocurred, with a significant part being made up by the Communist Party. A coup removed Prince Paul and restored Peter II’s power. Though British and perhaps Soviet intelligence was involved, much of it came from Yugoslavia and there were more pro-coup and pro-British demonstrations in the streets after it happened. However, the Axis soon invaded and occupied Yugoslavia. Puppet regimes were set up, in Croatia, the Independent State of Croatia. It was in fact a joint Italian-German puppet state until 1943 and Italy’s capitulation, when it became solely a German puppet (at this point, what remained of fascist Italy also became a German puppet). The Ustaše became the puppet government. The largest political legacy of this time was the impetus it provided to the communists. With Soviet backing, communists became the largest faction of the “partisans”, the Yugoslav armed resistance against the fascists. The government-in-exile, Democratic Federal Yugoslavia, was dominated by the communist Josip Broz Tito. When elections happened in 1945, they had their thumb on the scale and the opposition boycotted. Though Yugoslavia became a one-party communist state, it was not a Soviet puppet at any point, as Tito had won power himself rather than been given it through post-war treaties. The Communist Party of Yugoslavia (later the League of Communists of Yugoslavia (SKJ)) became the sole party, abolished the monarchy, and renamed the country the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. In 1948, Tito split from their main ally the Soviet Union, and pro-Soviets were purged. The party became the League of Communists, and the People’s Front the “Socialist Alliance of Working People”. Ethnic tension never went away, and the country remained federal. In 1971, the Croatian Spring saw the Croatian branch take nationalist reforms. Though Tito forced them to resign, the reforms stayed in tact. After Tito’s 1980 death, Yugoslavia remained a one-party state but lost its clear leader: instead of rotating presidency of the different ethnicities emerged. At the same time, communism was falling apart in Europe. In 1990, the Croatian SKJ branch, the League of Communists of Croatia (SKH) declared that the next election (to Croatia’s parliament) would be free and fair. The Croatian and Slovene branches then left the SKJ, and the Croatian one tried to paint itself as the bringer of reform by adding the subtitle “Party of Democratic Changes” (becoming the SKH-SDP). However, the SKH-SDP lost the election to the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ). It was led by Franjo Tuđman, a key figure in the Croatian Spring, who became President. The new HDZ government would remove communist national symbols, including renaming the region the Republic of Croatia. In 1991, an independence referendum was held, which passed with 93.2% support. The first elections in the current, independent Croatian state were in 1992. However, the country was not unified, as the Serb minority were against independence. Every part of Yugoslavia apart from Serbia and Montenegro had declared independence, and the Serbs in Croatia wanted to stay with the new Serbian state. They created a Republic of Serbian Krajina, which was unrecognised but functioned in large parts of Croatia for years. In the election, the HDZ won easily, with the nearest opposition on just fourteen seats. A 1995 offensive ended the Republic of Serbian Krajina, reunifying Croatia (a process that formally ended in 1998). Under this wave, Tuđman’s HDZ won another majority, with still no one opposition party doing well. However, he was beginning to rule illiberally: when the opposition won mayoral elections in the capital Zagreb, he refused to confirm their mayor, and appointed an ally as interim mayor. He also suppressed free media and turned state media into propaganda unlike that in Yugoslavia. When Tuđman died in 1999, much of his powers were transferred to the premiership, and the presidency became less powerful. Meanwhile, the SKH-SDP had dropped the SKH part, and then changed the acronym SDP to mean Social Democratic Party, which merged with another party to become the Social Democratic Party of Croatia. They had been one of the opposition forces to Tuđman, but nothing more than that. However, before the 2000 election, they joined with the centre-right Croatian Social Liberal Party (HSLS) and two small regionalist parties, and won close to a majority. The HDZ was finally defeated, and another five-party coalition led by the liberal farmers’ Croatian Peasant Party (HSS) was third. They joined in coalition with the SDP, HSLS and others to form a supermajority that cemented a parliamentary system under SDP Prime Minister Ivica Račan. No single party would win a majority ever again. In 2003, the HDZ won the most seats, with the SDP’s coalition with three other parties in second, and the HSS and HSLS making big losses. The HDZ’s Ivo Sanader managed to become PM. In 2007, a two party system was cemented, as the HDZ stayed in the lead and the SDP made gains. Sanader stayed in power, but retired abruptly in 2009, and was soon jailed for huge corruption (he is still in prison to this day). His deputy Jadranka Kosor became PM, but the HDZ coalition lost the 2011 election to the SDP-led “Kukuriku Coalition” (named after the restaurant where it was formed, can be translated as Cock-a-doodle-doo in English). The SDP’s Zoran Milanović became PM. In 2015, the SDP’s Croatia is Growing coalition lost to the HDZ’s Patriotic Coalition, but neither won a majority. The conservative Bridge of Independent Lists came third. A HDZ-Bridge coalition was formed with independent Tihomir Orešković becoming PM. However, in 2016, the HDZ voted their own government down to try and get a better position. Little changed in the arithmetic between the HDZ coalition and the SDP’s People’s Coalition. HDZ leader Andrej Plenković became PM. In 2020, Plenković’s HDZ coalition defeated the SDP-led Restart Coalition again, although still without a majority, staying over the line thanks to the support of the reserved national minority seats. The right-wing nationalist coalition of Miroslav Škoro Homeland Movement (DPMŠ), named after its leader, came third. However, the SDP did score a win in 2020 when Zoran Milanović defeated HDZ incumbent Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović in the presidential election. Plenković leads the HDZ coalition of five parties, while the SDP’s coalition is named Rivers of Justice. Milanović wants to run as an SDP candidate, but could not unless he resigns the presidency. Instead, their main candidate is SDP leader Peđa Grbin. Other coalitions will be led by the Homeland Movement and the Bridge. Also, an SDP split, known simply as the Social Democrats, have been founded and will lead the Our Croatia list, but though this took a lot of MPs, it seems to lack momentum. The HDZ seem to be ahead still, and Plenković will help to build a third term once the vote is done.

On the same day, the Solomon Islands will hold general elections. The Islands became a British protectorate in 1893 following negotiations with Germany, who also had a presence in the area. Self-governance of any form did not come until 1960, when a Legislative Council was introduced, but even then few members were Islanders and none were elected. A new constitution came in 1964, with elections in 1965. Eight of 22 members of the Council would be elected, but only one directly in Honiara, with the rest being chosen indirectly by councillors. By 1967 fourteen of 29 were elected, and thirteen directly, with only the Eastern Outer Islands having the indirect method. In 1970, the Legislative Council was abolished and replaced by a Governing Council. A majority of seats were now elected. In 1973, the remaining indirectly elected seat was abolished. After this election, political parties began to emerge out of MPs, with the United Solomon Islands Party (USIP) and People’s Progressive Party (PPP). A new constitution in 1974 renamed the Governing Council the Legislative Assembly, and the PPP’s Solomon Mamaloni became Chief Minister. The PPP and USIP pretty much died after the 1976 election, where the Independent Group’s Peter Kenilorea became Chief Minister. In 1978, the Solomon Islands became independent, and Kenilorea Prime Minister. The first election as independent country to the renamed National Parliament was in 1980. Kenilorea formed a Solomon Islands United Party (SIUP), with what was left of the PPP merging to form the People’s Alliance Party (PAP). The SIUP beat the PAP, but had no majority thanks to a large amount of independents. However, Kenilorea formed an alliance with independent members and remained PM. However, Mamaloni, now of the PAP, became PM again in 1981. The SIUP won the most seats (one more than the PAP) in the 1984 election and managed an alliance to get Kenilorea back in. However, in 1986 he resigned due to an aid controversy and his deputy, independent Ezekiel Alebua took power. The 1989 election saw a landslide win for the PAP, and the SIUP joining the ranks for the minor parties. Mamaloni became PM again. However, Mamaloni then left the PAP, but remained as PM, dismissing PAP figures and putting opposition figures in their place. In 1993, the PAP lost to Mamaloni’s new SIGNUR (Solomon Islands Government of National Unity, Reconciliation, and Progress Party). However, SIGNUR did not get a majority and the opposition formed a National Coalition around Francis Billy Hilly. Mamaloni managed to win back power in 1994 through parliamentary arithmetic. In 1997, his Solomon Islands National Unity and Reconciliation Party (SINURP) won the most seats but narrowly lost power to a disparate coalition of various opposition parties. The Solomon Islands Liberal Party (SILP) won just four seats, but that party’s Bartholomew Ulufa’alu became PM. In 2000, he was kidnapped by the Malaita Eagle Force (MEF), a militant organisation of Malaitans. Malaitans had often migrated to other parts of the Solomon Islands, and ethnic tension broke out under Ulufa’alu’s government. The MEF accused Ulufa’alu of not doing enough to support Malaitans despite being one himself, and the price for his release was his resignation. He was replaced by Manasseh Sogavare, of the small People’s Progress Party (PPP). In 2001, the PAP finished ahead of the Association of Independent Members (AIM) and Liberal Party-led Solomon Islands Alliance for Change (SIAC). The PAP’s Allan Kemakeza became PM. In 2006, no party won more than four seats, with independents winning a majority. AIM independents elected Snyder Rini PM, but this led to riots in the country’s Chinatown, due to Islanders viewing him as too pro-Chinese. Australian and New Zealander peacekeeping forces were needed to stop the riots, and Rini was soon removed after just two weeks in office. Instead, Sogavare returned, this time representing the Solomon Islands Social Credit Party, who won two seats. However, in 2007, Sogavare was removed by opposition in a parliamentary vote. The SILP’s Derek Sikua then became PM until the next election, in 2010. Independents were still the largest group, but the Solomon Islands Democratic Party at least won twelve seats. The Reform Democratic Party (RDP)’s Danny Philip became PM. After several supporters defected, he resigned in 2011. A National Coalition for Reform and Advancement was formed, under Gordon Darcy Lilo. In 2014, independents were again the only large faction. One of them, Sogavare, became PM again. However, he lost parliamentary support in 2017, and Rick Houenipelwa of the Democratic Alliance Party (DAP) became PM. In the 2019 election, eight parties won seats, but none won more than eight, and 21 of fifty seats were won by independents. Independent Sogavare formed a coalition with other independents and small parties, which he called the Democratic Coalition Government for Advancement (DCGA). This has stayed in power for the whole term, the first premiership to do so since Kemakeza’s in the 2001-2006 term. Sogavare then revived the Ownership, Unity and Responsibility Party (OUR Party) which is contesting the elections. The weak party system means parliamentary arithmetic is crucial. Sogavare severed the Islands’ traditional relations with Taiwan in favour of China, which was very controversial and led to protests which turned violent, mostly by Malaitans. They needed Australian, Fijian, Papua New Guinean and New Zealander forces to help put the riots down. Sogavare survived this, and after the riots, they signed a security deal with China, which was even more controversial. This led to anger from the opposition and traditional diplomatic allies of the Islands such as the United States, Australia, and Japan. However, it did lead to a greater American presence, including a new embassy, perhaps showing a wiliness and ability to play the major powers against each other for favours from both. That said, the opposition wants to repeal the pact. The election was also controversially delayed by a year, with Sogavare’s official reasoning that it was impossible to hold this and the Pacific Games in the same year. Sogavare has now led a campaign of criticising democracy, which leads to “moral decline”, and praising the Chinese system instead.

On 19 April, India holds the first phase of its general election. Today’s India had been split into various kingdoms, and colonial powers also had an interest. A dominant force was the British East India Company. However, an uprising led to the Government of India Act 1858, which gave the UK direct rule over India in the British Raj (British Rule). Elections in the British Raj were held for the first time in 1920. However, a growing political force, the Indian National Congress (INC), was only interested in party politics as a secondary concern, instead leading protest movements for India’s independence. Elections were held delayed by World War II, and held again in 1945. The INC won a majority, but the All-India Muslim League (AIML) won most Muslim seats. This was a clear mandate for independence, but a dual independence: the Muslim countries became Pakistan (today’s Pakistan and Bangladesh), while the rest became India. The leader of the INC, Jawaharlal Nehru, was named Prime Minister of the interim government which led India to independence in 1947, and remained Prime Minister after that. Elections were not held again until 1951, spilling over to 1952. The INC won a landslide majority in this election. The same happened in 1957, and 1962. There were some opposition parties that did well in certain areas, but none had the national presence Congress did. Nehru continued as Prime Minister until his death in 1964. Lal Bahadur Shastri, who served in a number of ministerial roles, became PM, but died himself in 1966. After that, Shastri’s Information Minister (and Nehru’s son) Indira Gandhi became PM. The INC won another majority in 1967. In 1969, Gandhi was expelled from the INC for violating party discipline when she supported a non-INC candidate for President. However, much of the party went with her, forming a new Indian National Congress (R) (INC (R), the R stood for Requisition). The INC (R) won a landslide while the rump Indian National Congress (O) (INC (O), the O standing for Organisation) were routed. Gandhi was criticised for using state machinery to aid her election, and a case against her was heard in 1975: she was convicted and unseated. However, she declared a state of emergency instead, leading to a period known as The Emergency, allowing her to rule by decree and suspend civil liberties. This lasted until the 1977 elections, where the INC (R) lost to the Janata Party (JP, People’s Party) of Morarji Desai, an alliance of multiple parties including the INC (O). However, apart from opposition to Gandhi they had little in common and in 1979 the squabbling led to several politicians splitting. Charan Singh formed the Janata Party (Secular) or JP(S) with the support of Indira Gandhi, whose INC (R) became the INC (I): the I standing for Indira. However, Singh refused to drop Gandhi’s charges, so the INC (I) withdrew support, and elections were held again in 1980. The INC (I) won a big victory, with both the JP and JP(S) getting nowhere. Gandhi became PM again. However, she was assassinated by bodyguards in 1984. The bodyguards where Sikhs, who had long clashed with Gandhi’s governments. Sikhs wanted more autonomy for the state of Punjab, the only state with a Sikh majority. This was rejected, leading to the growth of separatism and militancy. With militants hiding in a holy site, the government launched Operation Blue Star, using heavy weapons to get their man, leading to bloodshed, although the Indian side claimed the militants were using pilgrims as human shields. Whichever side people believed, this incident damaged Sikh relations with the Indian state, and led to the assassination, which only worsened things. Gandhi’s son Rajiv Gandhi became PM. The INC (I) won a massive majority in the election that year amongst anti-Sikh riots throughout the country. However, by 1989 he was battling away scandals that had affected him. One of the main critics came from within his own government in Finance Minister V. P. Singh (Vishwananth Pratap Singh) who resigned, formed his own party, and merged with the JP, JP(S) and other parties to form the Janata Dal (JD, People’s Party). Meanwhile, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP, Indian People’s Party), also emerged. Right-wing Hindu nationalism had existed in India, and though it joined the JP opposition during the Emergency, it found itself unable to assimilate with what was ultimately a secular movement based on old Congress principles. In the 1989 election, the INC was still the largest party, but without a majority, the JD was second and BJP third. Singh became head of a so-called National Front between the JD and regional parties, and became Prime Minister with the support of the BJP and external support from left-wing parties. However, the BJP’s Hindu nationalist agitation led to the Ram Rath Yatra (Rama Chariot Journey), a religious-political rally to the supposed birthplace of the Hindu deity Rama, where a mosque existed. Before the BJP President could get there, he was arrested for “fermenting communal tension”, and police fired at supporters still there. This led to the BJP withdrawing support and the end of the Singh government. Soon, Chandra Shekhar, which had led the JP for a long time before joining the JD, formed the Samajwadi Janata Party (Rashtriya) (SJP(R), Socialist People’s Party (National)) with INC (I) support. In 1991 the INC (I) withdrew support, and elections were held again. The INC (I) made gains, with the BJP the main opposition ahead of the Janata Dal. P. V. Narasimha Rao (Pamulaparthi Venkata Narasimha Rao) became PM, leading an INC (I) minority government with support of other parties. This government was not the most stable, but did complete a full term until 1996. This was a close race where the BJP won the most seats, but the INC (I) the most votes. A number of other parties like the JD won enough to be kingmakers, but no one party could give enough seats to either alone. As the leader of the largest party, the BJP’s Atal Bihari Vajpayee became PM to form a government, but the BJP were still considered too radical and Vajipayee resigned after two weeks. Minor parties formed a coalition called the United Front, with INC support (the original name having been restored after the election), and the JD’s H. D. Deve Gowda (Haradanhalli Doddegowda Deve Gowda) became PM. However, the INC (I) withdrew support in 1997. They agreed to give support back, in exchange for more sway and a new PM, which was External Affairs Minister Inder Kumar Gujral. However, the leaking of a report that criticised some members of the United Front for tacitly supporting Tamil militants in Sri Lanka who assassinated Rajiv Gandhi, the INC withdrew support again, and elections were held once more in 1998. Again, the BJP won the most seats, but the INC the most votes. Both parties gained and smaller parties were squeezed. Vajpayee became Prime Minister, forming a coalition called the National Democratic Alliance (NDA). However, when a small party pulled out, the BJP lost their majority and elections were needed again in 1999. Again, the BJP won the most seats and the INC the most votes. This time, Vajipayee’s NDA coalition lasted until 2004 elections. That election was very close between the INC and BJP. However, the INC coalition (the United Progressive Alliance or UPA) managed to form government with support of left-wing parties under Manmohan Singh. The INC/UPA won a bigger victory in 2009. By now, it was a clear two-party system: the INC-led UPA and BJP-led NDA. However, in 2014 the INC were destroyed and the BJP won a majority on their own. The INC were barely above the small parties in their seat count. Narendra Modi became PM. In 2019, though the INC/UPA recovered a little bit (not much), the BJP won another majority on their own. Modi has been a controversial figure due to the Hindu nationalist agenda being seen as discriminating against Muslims, and the weaponisation and centralisation of the state leading to a decline of democratic norms. However, he is also very popular amongst the Hindu majority, and is seen as raising India’s global clout and stature. This time, the NDA is up against the Congress-led Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance. The acronym, INDIA, may be a response to the Modi government using the name Bharat for the country even in English, which is said to have political overtones. It was basically a combination of the UPA and some left-wing parties. Former Minister Mallikarjun Kharge is the bloc’s leader. The NDA still has a lead in polls, though the INDIA alliance is hoping to be a stronger opposition this time. India is holding its election in phases, with the first phase taking all seats in Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Sikkim, Tamil Nadu, Uttarakhand, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Lakhshadweep, and Puducherry, and some parts of Assam, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Manipur, Rajasthan, Tripura, Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal, and Jammu and Kashmir.

On the same day, the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh will hold elections to its Legislative Assembly. The area was known as the North-East Frontier Agency, and is subject to a territorial dispute with China (both the communist government in Beijing and nominally, the republican one on Taiwan), who call it South Tibet. However, it was given the Sanskrit name Arunachal Pradesh (Land of the Dawn-Lit Mountains) and it became a union territory (not yet a state) in 1972. Elections were held for the first time in 1978. This was just after the Emergency had ended and Indira Gandhi had been defeated by the Janata Party. The INC barely bothered, only running a single candidate, with the JP beating its main opponent the People’s Party of Arunachal (PPA). Prem Khandu Thungon of the JP retained his position as Chief Minister. In 1979, he was replaced by the PPA’s Tomo Riba, and in 1980 President’s rule was declared. A new election was needed amidst the chaos, and in 1980, by which time the national JP had declined, a new election was held. The INC (I) and PPA both missed a majority, with independents as kingmakers. After the election, defections gave the INC (I) a solid majority, and Gegong Apang became CM. Apang would dominate politics in the next years. The INC won easily in 1984, and in 1987, the territory became a state. Even during the time of the National Front government, in 1990 the INC under Apang easily beat the Janata Dal, and in 1995 no party apart from Congress had any singificant representation, although there were several independents. Apang rebelled against the national party and formed his own Arunachal Congress (AC) in 1996, taking most local INC members with him. However, a split emerged in the Arunachal Congress with the arrival of the Arunachal Congress (Mithi) or AC(M), which was led by Mukut Mithi. Though Mithi initially supported the Vajipayee (BJP) government, when they didn’t give him a ministerial post, he switched back to the INC and his party was reincorporated into the INC. Mithi had enough members to bring down the Apang government, and the INC won a landslide in the 1999 state election. Apang was still around as the only elected AC member. He managed to take some INC members with him and formed a coalition in 2003 to unseat Mithi called the United Democratic Front, which then merged into the BJP. After the UPA won the 2004 election, Apang moved his members back to the INC, and he won the state election later that year. However, state members of the INC removed him in 2007, replacing him with Dorjee Khandu, the Power Minister. Khandu’s INC won easily in 2009. However, he died in a helicopter crash in 2011. Power Minister Jarbom Gamlin replaced him, but was removed by former Urban Development Minister Nabam Tuki later that year. Even amidst the BJP national landslide in 2014, the INC won easily in the state election on the same day. The BJP did make some gains as opposition. A split in the party led to a political crisis and President’s rule being declared in 2016. This was because Tuki removed Health Minister Khaliko Pul, and he then alleged financial mismanagement for which he was expelled. This crisis was resolved when Pul recruited enough INC members to the hitherto basically dormant PPA, and became Chief Minister. However, in 2016 the constitutionality was questioned and the Supreme Court removed Pul, restoring Tuki. Tuki resigned days later and Pema Khandu, son of Dorjee Khandu, replaced Tuki as INC leader and Chief Minister. This was enough to convince the PPA members to rejoin Congress. However, then every INC MLA apart from Tuki quit the party to join the PPA. However, Khandu was then suspended by the PPA in a plot to change leader. He instead took most PPA MLAs to the BJP, and formed a BJP government. In 2019, Khandu’s BJP won a majority, while the other seats were split. The INC took four and the PPA one, with the Janata Dal (United) or JD (U), a party that is centre-left and mostly popular in the east as the main opposition on seven. The National People’s Party (NPP), which is a centrist party also big in the north-east won five. Two went to independents. However, the INC still won the second-highest vote share. The BJP are expected to win this election very easily. Ten of sixty seats will be elected unopposed as the opposition did not bother with a candidate. The JD (U) are not bothering either, and the main opposition will come from the INC and NPP, but the BJP will doubtless win easily. The BJP won easily in both seats in this state in 2019 general elections as well, even though Tuki was the INC candidate in Arunachal West.

On the same date, the Indian state of Sikkim will hold legislative elections. The kingdom of Sikkim was an independent state. It allied with the UK to protect it from Bhutan and especially Nepal, who had dominated the region, and after the UK’s victory in the Anglo-Nepalese War, the Sugauli Treaty ceded Sikkim to (British) India. It became a British protectorate, but still technically independent, and this situation was similar after Indian independence, with Sikkim a monarchy and Indian protectorate. General elections were held in the country for the first time in 1953. However, there was a split between the indigenous Bhutia and Lepcha communities, who were Buddhist, and the Hindu Nepalis. Seats were given on a sectarian basis: all six Bhutia/Lepcha seats were won by the Sikkim National Party (SNP), who wanted to keep Sikkim independence, while Nepalis voted for the Sikkim State Congress (SSC), who wanted to join India. Elections in 1958 and 1967 added seats but retained the sectarian voter system. The SNP and SSC were joined by the Sikkim National Congress (SNC), which was meant to be a non-sectarian republican and pro-India movement and took much of the SSC’s seats, but also some from the SNP. Elections were held once more in 1970, and 1973 (by which time the SSC had merged to become the Sikkim Janata Congress or SJC (Sikkim People’s Congress)). The victory of the monarchist SNP in 1973 led to riots from those who thought the election was rigged. This led to a three-way agreement between India, the monarchy, and the parties for responsible government. The SNC dominated the 1974 elections and the SNP barely even bothered to campaign. It was clear time was up for the monarchy, and in 1975, Indian troops entered the country and held a referendum to abolish the monarchy, with 97.6% in support. The referendum was held under an atmosphere of intimidation and repression of opposition, but nonetheless it was upheld, and Sikkim became an Indian state in 1975, with the monarchy abolished. The SNC’s Kazi Lhendup Dorjee became Chief Minister, and merged his party into the INC. However, with the split in the INC around the time of the Emergency, the government lost its majority and the state was placed under President’s rule in 1979 for new elections. This was won by the Sikkim Janata Parishad (SJP, Sikkim Popular Association), while the main opposition was the Sikkim Congress (Revolutionary) (SC (R)). The rump INC was very weak and didn’t win a single seat. The SJP’s Nar Bahadur Bhandari became Chief Minister and merged the party back into the INC. However, he left the INC in 1984 to form the Sikkim Sangram Parishad (SSP, Sikkim Popular Struggle). This cost him his job as CM, with B. B. Garung (Bhim Bahadur Garung) becoming CM briefly. However, as the INC no longer had a majority, there was instability and the state was put under President’s rule again until new elections in 1985. Here, the SSP won a landslide, with every seat bar two (one INC, one independent). Bhandari became CM again. In 1989, the SSP won every seat. However, rumblings of discontent led to defections and in 1994, Bhandari was removed by a vote of no confidence. Sanchaman Limboo of the SSP became CM until elections later that year. Bhandari’s own Industries and Information Minister Pawan Kumar Chamling had split from the SSP to form the Sikkim Democratic Front (SDF) which defeated the SSP in the 1994 race. Chamling became CM. In 1999, the SDF increased their victory over the SSP, and by 2004 the SSP had all but disappeared. The SDF won every seat bar one for the INC. The SDF won every seat in 2009, and in 2014 won again, but were challenged by the Sikkim Krantikari Morcha (Sikkim Revolutionary Front, SKM), a left-wing party, who took ten seats. In 2019, the SDF and Chamling were finally removed by the SKM, who won the race seventeen seats to fifteen. Prem Singh Tamang became CM. In the general election, the SKM beat the SDF to the parliamentary seat by 167 thousand votes to 154.5 thousand. The BJP candidate got 16.5 thousand. The SKM and SDF will look to continue their spat here, but they may be swept away by the BJP, who are targeting this state, with national politicians including Prime Minister Narendra Modi visiting the state. It remains to be seen if the SKM/SDF vote can hold up from this onslaught.

On 21 April, the Maldives will hold parliamentary elections. The elections were delayed from March because of Ramadan. The Buddhist Kingdom of Maldives was converted into an Islamic Sultanate of Maldives in 1153. The Portuguese, who had a colonial interest in nearby Goa (modern-day India) had an outpost, but attempts to convert the islands to Christianity led to their expulsion. The Netherlands, who controlled Ceylon (modern-day Sri Lanka), managed to have influence by the seventeenth century, but they were removed in the Napoleonic Wars by the UK. The Maldives became a British protectorate. Throughout this time, the Maldives retained control of its own affairs, though with the British influence strong. Maldives got independence in 1965. In a 1968 referendum, 81.2% voted for a republic. The first presidential election was in 1968, and parliamentary elections were held in 1969. Long-time Prime Minister Ibrahim Nasir became the first President, as the only candidate. In 1975, he arrested Prime Minister Ahmed Zaki for being too popular, and threatening his rule, and had him exiled to a remote location in a coup. However, by 1978, Nasir’s popularity had fallen due to economic problems, so he did not stand in the election and soon flew to Singapore before authorities found out that he had embezzled money. Maumoon Abdul Gayoom, his Minister of Transport, was the only candidate for President. The same was true in 1983, 1988, 1993, 1998, and 2003. There were no parties at this time in parliamentary elections. However, agitation for political change led to the legalisation of political parties in 2005. The government forces became the Dhivehi Rayyithunge Party (Maldivian People’s Party, DRP), while the liberal opposition became the Maldivian Democratic Party (MDP). 2005 elections saw support for both the government and opposition, with the government favoured slightly. A 2007 referendum saw the presidential system retained with 62.0% support (the post of Prime Minister had long been abolished). In 2008 presidential elections, Gayoom led in the first round with the MDP’s Mohamed Nasheed second. Independent liberal Hassan Saeed came third, with the conservative Jumhooree Party (Republican Party) candidate Qasim Ibrahim in fourth. However, Nasheed won the second round with 54.2% of the vote, ending the thirty-year Gayoom administration. No party won a majority in the 2009 parliamentary election, but the DRP and MDP were still the strongest forces. In 2011, during the Arab Spring, protests occurred in the Maldives with some that endorsed Nasheed saying he failed to cement democracy, and others lamenting the economic situation. Nasheed resigned in 2012 with large pressure from the police and protestors (he claimed it was a coup) and Vice President Mohammed Waheed Hassan became President until 2013 elections. Waheed ran for re-election but came fourth behind Nasheed; Abdulla Yameen of the Progressive Party of the Maldives (PPM), which split from the DRP (who endorsed Waheed), and Ibrahim. A re-run was held of the first round due to irregularities but Waheed did not bother run again. Nasheed took the first round, with Yameen ahead of Ibrahim. However, Yameen won the runoff with 51.4% of the vote. The DRP had all but disappeared by the 2014 election, with most seats going to the PPM, MDP, and Jumhooree Party. In 2018, Yameen was defeated by the MDP’s Ibrahim Mohamed Solih, a longtime lawmaker, with 58.4% of the vote. In 2019, the MDP won a landslide in parliamentary elections, with 65 of 87 seats. There were eight candidates in 2023 for president, but the main ones were Solih and Mayor of Malé Mohamed Muizzu, who ran for the People’s National Congress (PNC). This was an ally of the PPM, and Muizzu won 54.0% support. However, after Muizzu took office, the PNC and PPM positions soured. The PNC and PPM are seen to be pro-China, whereas the MDP are pro-West and pro-India. Muizzu used the slogan “India Out” in his 2023 election campaign. This election therefore has a few parties: the PNC, PPM, and MDP among them.

On the same date, Poland will hold the second round of local elections. These will be in mayoral elections and other executive positions where no candidate received a majority. The PO Mayor of Warsaw Rafał Trzaskowski was re-elected in the first round easily, while it’s a friendly fight in Kraków where the PO and Left Together-endorsed independent candidates both beat the PiS nominee to third. In Wrocław, the Left and KO-backed incumbent Jacek Sutryk will go against Poland 2050 MP Izabela Bodnar, and in Łódź the PO incumbent Hanna Zdanowska also won in the first round. In Poznań the PO’s incumbent Jacek Jaśkowiak should easily beat PiS candidate Zbigniew Czerwiński, while in Gdańsk, KO independent Aleksandra Dulkiewicz won without needing a runoff, and the same was true about KO-backed independent Piotr Krzystek in Szczecin. In Bydgoszcz, PO incumbent Rafał Bruski won in the first round, as did his PO counterpart in Lublin Krzysztof Żuk. This shows the current coalition’s strength in urban areas, while the opposition PiS are stronger in rural parts of the country.